ENGLISH READING CIRCLE ON POETRY AND PROSE POETRY – POEM OF THE MONTH ANALYSIS: “BY THE WATERS OF BABYLON” BY EMMA LAZARUS

Our first poem for 2016 is “By the waters of Babylon,” by Emma Lazarus. It’s a long poem, broken up into different sections, and each section is written in prose. This makes it not quite an epic poem, although it does share the epic’s mythologizing impulses. The poem is a wonderful blend of tradition and innovation, and Lazarus’s real talent lies in the ways in which she plays with historical narratives, altering established versions of history in order to offer a new narrative, one that leads us to the very definition of America itself.

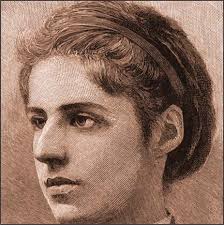

Lazarus was a Jewish American whose family traced their ancestry back to some of America’s first Jewish settlers. Her family were Sephardic Jews, Jews from Spain and Portugal, whose culture had flourished in the Iberian Peninsula for centuries well into the Middle Ages. Forced out of Spain and Portugal in 1492, Sephardic Jews established new communities in Europe and later in the Americas, particularly in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, or present-day New York.

It is this moment of exile that provides the starting point for “By the waters of Babylon.” Indeed, the title of the poem is taken from Psalm 137: “By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.” The Psalm expresses the lamentations of the Jews who have been exiled from Jerusalem, their homeland, and have been forced into captivity in Babylon; “How,” they ask, “shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?”

Lazarus, it seems, has found the answer. She uses poetry as a revisionary force to lead the Jewish people to a land that they can call their own: America. For something else happened in 1492 in the Iberian Peninsula. Christopher Columbus set forth from Spain on his expedition to the “New World,” an event which marked the beginning of European settlement in the Americas. Historically, these two events – the expulsion of the Jews and Columbus’s “discovery” of America – are not connected (as far as I know). Lazarus takes the liberty of very deftly bringing these two historical narratives into contact so that one journey coincides with another, and America becomes the place where the exiled Jews may find a home:

- Whither [Where] shall they turn? for the West hath cast them out, and the East refuseth to receive.

- O bird of the air, whisper to the despairing exiles, that to-day, to-day, from the many-masted, gayly-bannered port of Palos, sails the world-unveiling Genoese, to unlock the golden gates of sunset and bequeath a Continent to Freedom!

Lazarus further blurs the boundaries between history and mythology by collapsing the differences between three different periods of exile: that of the Biblical Jews in Babylon, the Sephardic Jews in the early modern era, and the Jews who were fleeing religious persecution in Russia and Eastern Europe in the late 19th century, many of whom eventually found refuge in the United States. Indeed, line 15 of Section I, “The Exodus (August 3, 1492),” seems to lack historical specificity, giving the reader the impression that we could be observing events from any moment in history: “The townsman spits at their garments, the shepherd quits his flock, the peasant his plow, to pelt with curses and stones; the villager sets on their trail his yelping cur [i.e., dog].”

This transhistorical quality contributes to the poem’s mythological narrative; and it is an example of Lazarus’s concern to establish a uniquely American literary and cultural tradition. She urged her contemporaries to stop looking to Europe for models of artistic and cultural greatness, and turn instead to “[t]his fresh young world [she saw], / With heroes, cities, legends of her own”? She played a role in this herself, with her poem “The New Colossus.” Engraved on a plaque at the base of the Statue of Liberty, “The New Colossus” – and in particular the lines “Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” – has been responsible for popularizing one of the most enduring myths of America: that it is a refuge for immigrants in search of freedom and a better life for themselves and their families.

Lazarus’s poetic vision is a unique blend of history, revision, and creative ingenuity, kind of like the America she believed in.

Happy Reading, Happy New Year, and see you on Monday,

Chiara